After many years of setting up projects for our industrial designers and mechanical engineers, here are my thoughts on some basic best practices on how to structure your files and keep your project organized. This segment examines a very useful tool for the engineering and product team: the costed BOM.

Here is the transcript of the podcast:

Here is the transcript of the podcast:

Good morning. My name is Montie Roland. I’m with Montie Design in Morrisville, North Carolina.

And this morning, what’d I’d like to talk about is how to structure your project from a file standpoint, from an organizational standpoint.

Montie Design is a full-service design firm in Morrisville, North Carolina. We provide industrial design, mechanical engineering and prototyping capability on-demand to help you move your project from concept to ready-for-the-shipping-dock.

So, we’ve talked about our Current Design, Released [directories]. . . let’s go back to Released for a second and talk about reving Assemblies or not to rev assemblies. It’s going to be driven by several things. One is if your design changed dramatically and the assembly doesn’t look like the parts, you need to rev the assembly. Other times you may need to rev the assembly is if you have a vendor that has a PLM system that is tied to the assembly rev. It doesn’t have the flexibility to control it without . . . to make a change to their drawing set without a revised assembly. We’ve seen that. We have a project right now we’re working on; they don’t have that control. So if we make changes we have to revise the assembly just because we revised a part. And the problem is that if you have to do that there may be a lot of subassemblies in-between; so it’s definitely a lot of work to do that.

And so you’re kind of starting to see, as a manager now, why sometimes your engineers are reticent to . . . to do revisions, because there is some work to it.

So other directories that you’ll need – one is that I create a “Project Management” directory. Project Management directory has contracts; has any schedules; things that you need in managing the project, but maybe not necessarily need to execute the design.

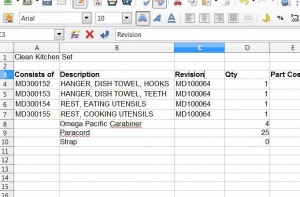

So another thing we would do is that we want to create a Bill of Materials. The Bill of Materials is sooooo handy. As the project goes along, you’re Bill of Materials is going to become a costed Bill of Materials. So at the end of the project, what we want to see is we want to see a . . . a Bill of Materials that has a part number, description, a revision, and has the costing information. Now, dependent on the project there may be some projects where that’s completed handled by the client. For a MontieGear project, one of the last steps is to make sure that Bill of Materials is correct, has the costing information, and then . . . that is used by the person doing the pricing, which often is me for MontieGear. I will take that, and if that Bill of Materials is done correctly, what I can then do is add the cost of labor to do assembly; any shipping costs; and then I know how to price the product without going through and pulling up a bunch of drawings. And this is so important later on. It saves tremendous amount of time.

So, as you go through the project, other directories you’re going to want to have is “Quotes”. So, every time a quote comes in, scan it in; if it’s electronic, save it. Create a directory of Quotes from your vendors in one spot. So, that’s a subdirectory under your Project directory. You’ve got Quotes. So, we’ve done Current Design, Concepts, Quotes. Another one you’ll often have is something called “Files from Client”. And so those are files that the client has provided. These are documentation that where they’ve given you pre-project documentation; there may be initial version of a product specification. And so this is that repository of those documents. Then again, a lot of times we’ll save those file names by date; if it’s a quote we’ll save it by date and vendor name and then possibly, you know, what that is if it’s a single pat quote. So you can quickly scan down that directory and find the quote for the lower left beam, or what have you.

And you may have other directories as needed. Those will depend with projects. One of the other things we do is create an images directory. And then the Images directory, underneath it, we’ll have a description of generally what that image is about. So, it might be /images/first prototype or date-first prototype. Date . . . Proof of Concept; Date-Alpha Prototype; Date-Beta Prototype; Date-Installation. So, that way you can scroll through there and quickly find those images. It’s also a great place if you’re . . . if you’re a manufacturer to also put your . . . your product shots, or your products-in-use. Maybe they’re static images done in the light tent. But that way you’ve got a great way to . . . to go find that because it’s tied to the project.

So this Project directly, theoretically, if you were to just copy that to a flash drive, it would have everything you need to continue with that project. And that’s good because over time hard drives change, files get deleted, directories get changed. So if you encapsulate everything in that subdirectory, then that makes life a lot easier.

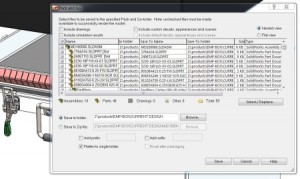

So, kind of to roll back through this, we’ve got parametric files and we’ve got non-parametric files. And then we’ve got files that are often edited. And so, the parametric files are Solid Works files that could be inventor; it could be Pro-E. But those are files that need to be kept together; need to be moved using a Pack and Go. And occasionally with your current design, one way to make sure you’ve got the correct files in there is to Pack and Go to a temporary directory; delete the files in Current Design; and then copy those back in. And that way you know you don’t have some superfluous files in there.

Other files that we’ll create and need to do something with are . . . are non-parametric files. So, these could be IGES, STEP, DXF, DWG. And these files, in the Release directory, it will have the parametric files, plus a PDF of each drawing and maybe a DXF or DWG, if that’s needed to do a cutting process, a 2-D cutting process, like water jet, or sometimes a machine shop if they’re working from a 2-D file.

Also have the 3-D non-parametric files, like STEP or IGES. And so that way, in that Release directory, you’ve got the CAD files, plus you’ve the file you’re going to send out to vendors, the non-parametric files. And probably this would be a good spot for your Bill of Materials for that Rev. And so, in this case, a lot of these files follow the same format. Its part number . . . for us, at least, its “part number – description_rev “ and then the two-digit revision code. So, 00 or 02. And so we do this to keep these file names consistent so they’re easy to read through quickly. And that way everything is . . . you get to . . . you can very quickly figure out what you’re looking for. If you don’t maintain control over file names, you end up with file names that mean something to one person today, but may mean nothing to someone later. And, six months’ from now, may not mean anything to the person who named it then. So, I think it’s very important to maintain that . . . that control; have a strict doctrine over that.

That Bill of Materials? It’s important for costing purposes if you’re a manufacturer, because that way you’re engineer is taking what they’ve learned when they went out for quotes, or the purchasing agents wouldn’t . . . so, whoever went out for those quotes enters that into your Bill of Material, so now you can do your pricing quickly without having to go look for a bunch of information which may be harder to find.

Also, storing those quotes is valuable because then that . . . because then you’ve got a way to address that quickly, there again, without having to go look through emails or . . . look wherever [other places on the server].

So, from a hundred thousand foot view, what we want to do is we want this project directly . . . directory to provide everything you need to pick up that project, modify that project, price that product, or deliver to a client. And if you can do that then that helps multiple phases of the organization; not just engineering or industrial design, but also purchasing; it’s great for a reference later, for sales and marketing, because they understand what’s driving the cost; and it’s just a win-win all the way around. And that . . . that’s important to main . . . there again, to maintain that discipline because it’s not only helping you in the engineering stage; like I said, you’ll reap benefits for . . . the life of the product, especially if you ever have to go back and make a change or you ever have to go back and re-price or pricing on components change. It’s a great tool. And having that in a standard format is . . . it just benefits you.

If you have any questions about this, please don’t hesitate to give me a call. I know it’s kind of a long section here and technical, but happy to entertain your calls, questions. It’s 1-800-722-7987. That’s Montie Roland. Email – montie (M-O-N-T-I-E)@montie(M-O-N-T-I-E).com. Or you can visit our website – www.montie.com. You can see the results of client work we’ve done at the montie.com website. Or you can see some of our projects that we’ve done for ourselves at montiegear (M-O-N-T-I-E-G-E-A-R).com.

I hope this has been beneficial. Montie Roland, signing out.